Death Row Exonerated by State A-H

Arizona:

Prison privatization, just like every other kind of privatization taking place in our nation, is becoming is becoming commonplace in the United States, and Arizona leads the way with nearly 30 percent of its prisoners housed in private facilities. The local prison industry is booming! In addition, Arizona can brag about being one of the states in the U.S. with the most death row exonerations.

Ray Krone is one of those eight men exonerated from death row in the state of Arizona. Twice convicted for a murder he did not commit, he spent more than a decade in prison before DNA testing cleared his name. He is the 100th former death row inmate freed because of innocence since the reinstatement of capital punishment in the United States in 1976. He was the twelfth death row inmate whose innocence has been proven through post conviction DNA testing. “I have the ability to be angry, but I’ve tried to avoid the anger. I sat in prison all that time, and I watched people who were so bitter and angry that they became victims. At some point you’ve got to take control of your life and rise above things. I hope I won’t ever get to the point where I am so overwhelmed with grief and tragedy that I would actually give in. [...]I would not trust the state to execute a person for committing a crime against another person. I know how the system works. I know what prison is like, I know what the judges are like, and I know what the prosecutors are like. It’s not about justice or fairness or equality. It’s absolutely wrong. Any chance I can, whether I start with one or two people or a whole auditorium filled with people, I’ll tell them what happened to me. Because if it happened to me, it can happen to anyone.” -- Roy KroneThe eight freed individuals are: Jonathan Treadway, Jimmy Lee Mathers, James Robison, Robert Charles Cruz, David Wayne Grannis, Christopher McCrimmon, Ray Krone, and Lemuel Prion. Here are two more examples:

Jonathan Treadway (Arizona, Conviction: 1975) is another man exonerated from Arizona's death row. Convicted of sodomy and first degree murder of a six-year-old and sentenced to death. He was acquitted of all charges at retrial by the jury after five pathologists testified that the victim probably died of natural causes and that there was no evidence of sodomy.

Jimmy Lee Mathers and two co-defendants were convicted and sentenced to death in the murder of Sterleen Hill. The Arizona Supreme Court reviewed Matthers case in 1990, and in reviewing the evidence; the Court found that there was a complete absence of probative facts to support Matthers conviction. The court stated that most of the evidence presented at trial had nothing to do with Mattthers conviction. The Court set aside Matters conviction and sentence and entered a judgment of acquittal. Links: Coalition of Arizonans to Abolish the Death Penalty (CAADP) is a statewide organization that works to end the death penalty in Arizona.

Alabama:

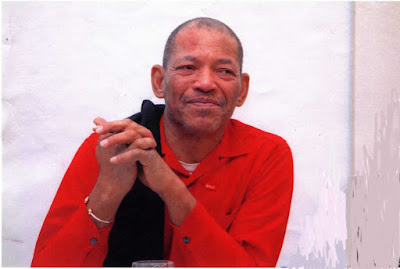

Walter McMillian, is one man of the seven men exonerated from death row, in the state of Alabama. McMillian, a black man, with no record, was convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of a 18-year old Rhonda Morrison, a young white woman who worked as a clerk in a dry clearing store in Monroeville, Alabama in 1987. Seven months after the Morrison murder, which had the police stumped, McMillian was arrested . At the time, the police had no motive, no fingerprints, no ballistics test, no physical evidence of any kind, linking McMillian to the crime...just the word of one person, Ralph Myers, a career criminal awaiting trial, facing a possible death sentence for murder. Using the death sentence as leverage to scare Meyrs, an agent of the ABI pressured McMillian to lie, promising him a reduced sentence of no more than 30-years. Held on death row prior to being convicted and sentenced to death, McMillian's trial lasted only a day and a half. Three witnesses testified against McMillian, and the jury ignored multiple alibi witnesses, who testified that he was at a church fish fry at the time of the crime. The trial judge overrode the jury’s sentencing verdict for life and sentenced McMillian to death. EJI's Bryan Stevenson took on the case in post conviction, where he showed that the State’s witnesses had lied on the stand and the prosecution had illegally suppressed exculpatory evidence. Mr. McMillian's conviction was overturned by the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals in 1993 and prosecutors agreed the case had been mishandled. Mr. McMillian was released in March 2003 after spending six years on death row for a crime he did not commit. Prior to McMillian's exoneration, the case was profiled on "60 Minutes" (below) on Nov. 22, 1992. and is the subject of a 1996 Edgar Award-winning book by Pete Earley entitled "Circumstantial Evidence."

Walter McMillian, is one man of the seven men exonerated from death row, in the state of Alabama. McMillian, a black man, with no record, was convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of a 18-year old Rhonda Morrison, a young white woman who worked as a clerk in a dry clearing store in Monroeville, Alabama in 1987. Seven months after the Morrison murder, which had the police stumped, McMillian was arrested . At the time, the police had no motive, no fingerprints, no ballistics test, no physical evidence of any kind, linking McMillian to the crime...just the word of one person, Ralph Myers, a career criminal awaiting trial, facing a possible death sentence for murder. Using the death sentence as leverage to scare Meyrs, an agent of the ABI pressured McMillian to lie, promising him a reduced sentence of no more than 30-years. Held on death row prior to being convicted and sentenced to death, McMillian's trial lasted only a day and a half. Three witnesses testified against McMillian, and the jury ignored multiple alibi witnesses, who testified that he was at a church fish fry at the time of the crime. The trial judge overrode the jury’s sentencing verdict for life and sentenced McMillian to death. EJI's Bryan Stevenson took on the case in post conviction, where he showed that the State’s witnesses had lied on the stand and the prosecution had illegally suppressed exculpatory evidence. Mr. McMillian's conviction was overturned by the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals in 1993 and prosecutors agreed the case had been mishandled. Mr. McMillian was released in March 2003 after spending six years on death row for a crime he did not commit. Prior to McMillian's exoneration, the case was profiled on "60 Minutes" (below) on Nov. 22, 1992. and is the subject of a 1996 Edgar Award-winning book by Pete Earley entitled "Circumstantial Evidence."

Daniel Wade Moore [Alabama Conviction: 2002, Acquitted: 2009] was acquitted of all charges by a jury in Alabama on May 14. Moore was originally found guilty of the murder and sexual assault of Karen Tipton in 2002. The judge overruled the jury’s recommendation of a life sentence and instead sentenced him to death in January 2003, calling the murder one of the worst ever in the county. A new trial was ordered in 2003 because of evidence withheld by the prosecution. (See State V. Moore, No. CR-04--0805, Ala. Ct. of Crim. App. (2206) (providing procedural summary at pp.2-3; the circuit judge's order for a new trial was upheld by the Ala. Supreme Court, State v. Moore, No. Ms. 1030218, Nov. 6, 2003)). A second trial in 2008 ended in a mistrial with the jury deadlocked at 8-4 for acquittal. Judge Glenn Thompson, who originally sentenced Moore to death, ordered a retrial upon discovery that the prosecution had withheld important evidence. "Orders were entered in any capital case, that whatever the state has, whatever the prosecutor has, whatever the investigation has they should provide that to the defendant," said Judge Thompson. The evidence missing was a 256-page F.B.I. report. "The prosecution, Mr. Valeska specifically, looked me in the eye and said, quote, 'there ain't no such thing as an F.B.I. report.' Well, there probably wasn't a report, but there were 256 pages of information collected by Decatur police officers that were sent to the F.B.I.," said Judge Thompson. According to Judge Thompson, Assistant Attorney General Don Valeska later came to him confessing there was withheld information. "Mr. Valeska came forward with the information after the conviction," said Judge Thompson. “Clearly, the only remedy was to grant him a new trial and I did," he said. "It frustrated and angered me that he would be willing to lie to the court," he continued. Meanwhile, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals ordered Judge Thompson to stand down from the trial and continued to let Valeska prosecute Moore. Upon hearing the jury’s not guilty verdict, Judge Thompson responded, "I felt like it was the only conclusion that a jury could reach if they actually followed the law." Thompson also said that the problems with the prosecution withholding evidence continued throughout the 10 years of the case. Just days before the current trial started, the prosecution called the defense saying they had just found new evidence from the victim's home computer.

California:

Ironically, California, the epitome of over-incarceration, who has been ordered by the courts to bring down the population of its prison system - due mostly to the state's deeply misguided three-strikes law, which puts people behind bars for 25 years to life if they commit a third felony, even a nonviolent one - to alleviate its badly overcrowded conditions, is also the state where the Supreme Court declared, in California v. Anderson (Cal. 1972), that the Death Penalty was unconstitutional, and in violation of what was then Article 1, Section 6 (now Article 1, Section 17) of the State Constitution, and that the decision was retroactively effective to all persons on Death Row in the State. Later that year, the U.S. Supreme Court in Furman v. Georgia (1972) would also find the death penalty unconstitutional.

Ernest (Shujaa) Graham . Shujaa Graham was born in Lake Providence, LA, where he grew up on a plantation. His family worked as share-croppers, in the segregated South of the 1950s. As a teenager, Shujaa lived through the Watts riot and experienced the police occupation of his community. In and out of trouble, he spent much of his adolescent life in juvenile institutions, until at age 18, he was sent to Soledad Prison. In 1961, he moved to join his family who had moved to South Central Los Angeles, to try to build a more stable life. In prison, Shujaa, mentored by the leadership of the Black Prison movement, he taught himself to read and write, and studied history and world affairs, becoming a leader of the growing movement within the California prison system, as the Black Panther Party expanded in the community. In 1973, Shujaa was framed in the murder of a prison guard at the Deul Vocational Institute, Stockton, California. As a recognized leader within and without the prison, the community became involved in his defense, and supported him through four trials. Shujaa and his co-defendant, Eugene Allen, were sent to San Quentin's death row in 1976, after a second trial in San Francisco. Shujaa spent three years on death row, but he and Eugene Allen continued to fight for their innocence. A third trial ended in a hung jury, and after a fourth trial, they were found innocent in 1979, after discovering that the District Attorney excluded all African American jurors, the California Supreme Court finally overturned the death conviction. As Shujaa often says, he won his freedom and affirmed his innocence in spite of the system. He was released and exonerated in March, 1981, and continued to organize in the Bay area, building community support for the prison movement, as well as protest in the neighborhoods against police brutality. In the following years, Shujaa moved away from the Bay area. Shujaa learned landscaping, and created his own business. He and his wife raised three children, and became part of a progressive community in Maryland. In 1999, Shujaa was invited to speak about his experiences on Death Row at fund raiser for the Alabama Death Penalty project, sponsored by the New York Legal Aid Foundation. This was a new beginning, and provided Shujaa the opportunity to begin to tell his story, his experiences and grow through work with other death penalty opponents.

Ernest (Shujaa) Graham . Shujaa Graham was born in Lake Providence, LA, where he grew up on a plantation. His family worked as share-croppers, in the segregated South of the 1950s. As a teenager, Shujaa lived through the Watts riot and experienced the police occupation of his community. In and out of trouble, he spent much of his adolescent life in juvenile institutions, until at age 18, he was sent to Soledad Prison. In 1961, he moved to join his family who had moved to South Central Los Angeles, to try to build a more stable life. In prison, Shujaa, mentored by the leadership of the Black Prison movement, he taught himself to read and write, and studied history and world affairs, becoming a leader of the growing movement within the California prison system, as the Black Panther Party expanded in the community. In 1973, Shujaa was framed in the murder of a prison guard at the Deul Vocational Institute, Stockton, California. As a recognized leader within and without the prison, the community became involved in his defense, and supported him through four trials. Shujaa and his co-defendant, Eugene Allen, were sent to San Quentin's death row in 1976, after a second trial in San Francisco. Shujaa spent three years on death row, but he and Eugene Allen continued to fight for their innocence. A third trial ended in a hung jury, and after a fourth trial, they were found innocent in 1979, after discovering that the District Attorney excluded all African American jurors, the California Supreme Court finally overturned the death conviction. As Shujaa often says, he won his freedom and affirmed his innocence in spite of the system. He was released and exonerated in March, 1981, and continued to organize in the Bay area, building community support for the prison movement, as well as protest in the neighborhoods against police brutality. In the following years, Shujaa moved away from the Bay area. Shujaa learned landscaping, and created his own business. He and his wife raised three children, and became part of a progressive community in Maryland. In 1999, Shujaa was invited to speak about his experiences on Death Row at fund raiser for the Alabama Death Penalty project, sponsored by the New York Legal Aid Foundation. This was a new beginning, and provided Shujaa the opportunity to begin to tell his story, his experiences and grow through work with other death penalty opponents.

Oscar Lee Morris was wrongly convicted of murder in 1984 and sentenced to death. He spent six years on death row and re-sentenced to life in prison in 1990 and was finally freed in 2000 after 16 years in prison. Early on the morning of September 3, 1978, William Maxwell was shot to death at a Long Beach, California bathhouse, which was known to be a popular meeting place for homosexuals. Police arrived at the scene moments after the shooting, and questioned a witness who saw the back of the shooter, but no one was arrested. Several months later, a man named Joe West contacted the police to tell them that his friend Oscar Lee Morris had murdered Maxwell. West said he had dropped Morris off at the bathhouse that day and given him the murder weapon; he claimed Morris said he “had to kill” a homosexual. West had known Morris since childhood, and the two men had a falling out shortly before West went to the police. Police began investigating Morris, but in 1979 the detectives were pulled from the case, and it was mistakenly filed as a closed case. Investigation came to a halt until 1982, when Joe West was arrested for auto theft and joyriding. He once again told police that Morris had killed Maxwell. Morris was charged with Maxwell’s murder shortly afterwards. West was the key witness for the prosecution at Morris’s trial. He testified that he received nothing from the state in return for his testimony, though it was later revealed that in fact West’s sentence for an auto theft charge had been reduced and his sentence for a parole violation had been terminated. Morris was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death in March 1983. In 1988, the Supreme Court of California reduced Morris’s death sentence to life without parole, finding that there was no evidence that the murder had been committed during a robbery, a necessary condition for his capital sentence. In 1997, on his death-bed, West recanted his testimony against Morris. Based on this new evidence, the Supreme Court of California ordered an evidentiary hearing in 1998, and the Los Angeles County Superior Court granted Morris a new trial. Prosecutors declined to retry the case, and Morris was freed in 2000. Morris filed a lawsuit against the city in 2002, but received no relief.

“Morris’s case was marked by the controversial use of testimony from a felon granted leniency for his testimony, and the prosecution’s failure to divulge this special relationship to the defense during the trial. The star witness later confessed that he had fabricated the entire case against Morris in return for favorable treatment in at least two criminal cases he was involved in.

The chief prosecutor in the case, Arthur Jean, Jr., is today a Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge. In a deposition about the case, Judge Jean said, “I wish I wasn’t on record having participated in giving him [Morris] something less than a perfect trial, but I am. It’s an embarrassing situation that I didn’t do well at the trial, and I didn’t handle things well. And misjudgments occurred, and I made them. And it’s tough to look people in the eye and ‘fess up with them sometimes.”

.... As a prosecutor, Mr. Jean had told the jury in Morris’s case that “there is no evidence, not a shred, and you would know if it existed, if Mr. West [the witness] got any benefit from the handling of his criminal case.” Records show that Mr. West in fact received a reduced sentence on a felony auto theft charge in return for his testimony against Mr. Morris, as well as termination of his prison sentence for parole violation. Mr. Jean’s handling of the Morris case drew the wrath of the California Supreme Court when it considered Morris’s automatic capital appeal and vacated his death sentence in 1988. Mr. Morris spent another 11 years in jail, until Mr. West recanted his testimony and Mr. Morris was released. (LA Daily Journal, Oct. 29, 2002)"

Patrick Croy In 1978, Patrick "Hooty" Croy was working as a logger in Yreka. A weekend of partying led to an ill-fated shoot out between police and a group including Croy. By the end, Officer Hittson was dead. Croy was convicted of attempted robbery and Officer Hittson's murder. The jury did not convict Croy of intentionally killing the offer, but, rather, convicted him based on the theory of felony murder -- that is, that he intentionally committed a robbery that resulted in the officer's death. Croy was sentenced to death. In 1985, Croy's conviction and death sentence were overturned. The California Supreme Court found that the trial judge had read the wrong instructions to the jury, allowing the jury to convict Croy of robbery even if he did not intend to steal. Because the murder conviction was based on the theory that Croy had intentionally committed a robbery that had caused the officer's death, the murder conviction too was reversed. The case was re-tried and Croy presented evidence that he acted in self-defense during the shoot out. The jury found him not guilty of the crime for which he had previously been sentenced to death. Croy was released in 1990 and today still lives in Yreka. For more, go to In his own words:

Patrick Croy In 1978, Patrick "Hooty" Croy was working as a logger in Yreka. A weekend of partying led to an ill-fated shoot out between police and a group including Croy. By the end, Officer Hittson was dead. Croy was convicted of attempted robbery and Officer Hittson's murder. The jury did not convict Croy of intentionally killing the offer, but, rather, convicted him based on the theory of felony murder -- that is, that he intentionally committed a robbery that resulted in the officer's death. Croy was sentenced to death. In 1985, Croy's conviction and death sentence were overturned. The California Supreme Court found that the trial judge had read the wrong instructions to the jury, allowing the jury to convict Croy of robbery even if he did not intend to steal. Because the murder conviction was based on the theory that Croy had intentionally committed a robbery that had caused the officer's death, the murder conviction too was reversed. The case was re-tried and Croy presented evidence that he acted in self-defense during the shoot out. The jury found him not guilty of the crime for which he had previously been sentenced to death. Croy was released in 1990 and today still lives in Yreka. For more, go to In his own words:

And then there is one death row inmate, Dennis Lawley - who the court allowed to defend himself regardless of the fact he was diagnosed a paranoid schizophrenic - who, despite recanted testimony, questions about a former district attorney who has died, and new evidence - the murder weapon the self-confessed murderer said he used - still resides on death row.

And then there is one death row inmate, Dennis Lawley - who the court allowed to defend himself regardless of the fact he was diagnosed a paranoid schizophrenic - who, despite recanted testimony, questions about a former district attorney who has died, and new evidence - the murder weapon the self-confessed murderer said he used - still resides on death row.

“I have at least a philosophical objection to begging these people for my life, and I am not going to do it. I'm not going to do it. I'm not going to do it." - Dennis Lawley, a paranoid schizophrenic defending himself after which he was sentenced to death.

Colorado:

The state of Colorado currently has three people on death row, and of the three, two are black and one is Latino. Colorado has executed one person since 1976. To date, no prisoner on Death Row has been found innocent in Colorado, however, the following five people were under sentence of death in Colorado, and have had their sentences overturned.

The Colorado Supreme Court ruled that the death sentences for three men, George Woldt, William "Cody" Neal and Francisco Martinez - imposed by three-judge panels were unconstitutional, citing a recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling that juries, not judges, must determine if the death penalty is appropriate. The Colorado Supreme Court ordered these three men be re-sentenced to life in prison without parole. In addition, the following also had their death sentences overturned.

Robert Harlan - In Harlan's case, jurors were improperly exposed to the Bible and passages describing God’s view on punishment as they deliberated. ... "If any case merits the death penalty, there cannot be serious debate about this case being that case," Judge John J. Vigil wrote. "The death penalty, however, must be imposed in a constitutional manner." "Jury resort to biblical code has no place in a constitutional death penalty proceeding."

Edward Montour Jr. represented himself and plead guilty in 2003 for the murder of a correctional officer. He continued to represent himself in the penalty phase, presented no mitigation, and was sentenced to death by Judge King of the Douglas County District Court. Continuing pro se, Mr. Montour then waived any post-conviction challenges and now seeks to waive any appeal other than the mandatory review by the Colorado Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has remanded the case to the District Court for determination of Mr. Montour's competency to waive his appeal, and counsel has now been appointed over Mr. Montour's objection to litigate the issue of competency. This case highlights the problem of so called "volunteers," or defendants who refuse both legal representation and fail to present any defense or mitigation. Although individuals have the right to represent themselves, if we have a death penalty, our system must find a way to see that mitigating information is brought before the court lest we simply have suicide via the State in such cases. A Colorado Supreme Court decision in April 2007, however, reversed the death sentence.

Connecticut:

Connecticut is one of two states in New England to maintain the death penalty. Amongst the 14 death sentences, one execution in 2005, since 1973, and ten individuals (highest percentage who are minorities, 70%) sitting on Connecticut 's death row, no one has been exonerated. Last year, long-time supporter of capital punishment, Republican Gov. M. Jodi Rell vetoed a bill that would have abolished the death penalty in Connecticut, but with Rell's announcement she will not seek reelection, a change in leadership imminent, State Rep. Michael Lawlor said there could be a shift in the death penalty law. Lawlor said that there is more than enough bipartisan support in both the state's House and Senate to pass another bill to abolish the death penalty and if Rell's successor also supports abolishment, it won't be long before the law is repealed. Amnesty International released the following statement regarding that decision:

"Governor Rell's veto of this legislation represents a missed opportunity for the state of Connecticut to extricate itself from the useless and costly boondoggle that is capital punishment. Any other policy that wasted valuable taxpayer dollars without reducing crime or making anyone safer would have been eliminated without hesitation. "No system can be perfected enough to prevent the innocent from being sent to death row. Recent cases have demonstrated the fallibility of Connecticut's justice system. In the last two years James Tillman, who was given 45 years for rape, and Miguel Roman, who was sentenced to 60 years for murder, were found to be have been wrongfully convicted. The exonerations of these innocent men ought to make Governor Rell realize that the irreversible punishment of death has no place in a system that makes such mistakes.''Currently, Republican legislators are proposing legislation intended to speed up executions. One of the bill’s sponsors concedes that passage is unlikely, but the proposal ensures capital punishment will get a public hearing in the run-up to the 2010 elections for General Assembly.

F l o r i d a:

Since Jeb Bush was elected governor of Florida, he has attempted to do everything in his power to speed up executions, disregarding the fact that Florida leads the nation with 23 death row exonerations, out of 139 nationwide according to Death Penalty Information Center. What is it with the Bushs and racking up executions? Serial killer genes, perhaps? Florida death row exonerations: David Keaton was the first person exonerated from Death Row in the United States, when it was discovered he was wrongly convicted, in 1971, on the basis of mistaken identification and coerced confessions, Keaton was sentenced to death for murdering an off duty deputy sheriff during a robbery. The State Supreme Court reversed the conviction and granted Keaton a new trial because of newly discovered evidence. The actual killer of the sheriff was later convicted.

Juan Melendez spent 17 years on death row for a 1983 murder to which another man had repeatedly confessed -- evidence prosecutors withheld. On January 3, 2002 Juan Melendez became the 24th person to be released from death row in the state of Florida, the 99th Nationwide.

Rudolph Holton spent 16 years on Florida's death row. On January 24, 2003, he was released, the 25th person wrongly convicted and sentenced to death by the state of Florida. In Holton's case, prosecutors had withheld evidence, a DNA test had been falsified, and the jailhouse snitches who testified against him later admitted they were lying. At the very least, one would think, after an innocent man's release from 16-years on death row, political leaders would do everything in their power to make sure they are devoting adequate resources to death penalty cases. Florida's Governor, Jeb Bush, apparently disagrees. At the time of Holton's release, he announced a 40% cut in state funding for legal services for those facing the death penalty, and renewed his call for a time limit on death row appeals. Requiem for Frank Lee Smith (PBS Frontline) - Mr. Smith spent 14-years on Florida's death row for a crime he did not commit. Unfortunately, Mr. Smith died of cancer before he was proven innocent. "In December 2000, after spending 14 years on Florida's death row, Frank Lee Smith was finally cleared of the rape and murder of 8-year-old Shandra Whitehead. Like nearly 100 prisoners before him, Smith's exoneration came as a result of sophisticated DNA testing unavailable when he was first convicted. But for Frank Lee Smith, the good news came too late: Ten months before he was proven innocent, Smith died of cancer in prison, just steps away from Florida's electric chair." According to Southern Newspaper Coverage of Exonerations from Death Row, "exonerated inmates receive less coverage than those who are executed, coverage is apt to portray the exoneration as the result of an isolated mistake and not indicative of systematic failure, and coverage emphasizes the experiences of former inmates after being released, not during their incarceration. Cumulatively, this pattern serves to minimize the seriousness of the innocent on death row situation, and is consistent with media theories suggesting political coverage is generally supportive of moderatism/ mainstream elite political thinking."

Delbert Tibbs, was born in what he describes as Apartheid Mississippi, before the coming of "the King and Mrs. Parks". He moved to Chicago at the age of twelve with his widowed mother. He attended Southeast City college and Chicago Theological Seminary. After dropping out in 1972, Delbert began what he has described as his "Wilderness Experience", walking around the U.S.A. Mr. Tibbs, who was a black theological student at the time of his arrest, was sentenced to death for the rape of a sixteen-year-old white girl and the murder of her companion. He was convicted by an all-white jury on the testimony of the female victim whose testimony was uncorroborated and inconsistent with her first description of her assailant. The conviction was overturned by the Florida Supreme Court because the verdict was not supported by the weight of the evidence

Delbert Tibbs, was born in what he describes as Apartheid Mississippi, before the coming of "the King and Mrs. Parks". He moved to Chicago at the age of twelve with his widowed mother. He attended Southeast City college and Chicago Theological Seminary. After dropping out in 1972, Delbert began what he has described as his "Wilderness Experience", walking around the U.S.A. Mr. Tibbs, who was a black theological student at the time of his arrest, was sentenced to death for the rape of a sixteen-year-old white girl and the murder of her companion. He was convicted by an all-white jury on the testimony of the female victim whose testimony was uncorroborated and inconsistent with her first description of her assailant. The conviction was overturned by the Florida Supreme Court because the verdict was not supported by the weight of the evidence

Wilbert Lee and Freddie Pitts (left) were beaten, denied legal counsel, and threatened with death if they didn't sign "confessions" for the 1963 robbery and murder of two Port St. Joe gas station attendants. Within 28 days, an all white jury, white judge, white prosecutor, white policeman -- convicted both of them, sending them off to die in Florida's electric chair. While all this transpired, the real killer, Curtis Adams Jr., a white man who had already been convicted of another murder continued his killing spree. Florida's governor Reubin Askew, who served from 1971 through 1978, in 1975 approved a full pardon for Freddie Pitts and Wilbert Lee, who had spent 12 years in prison, eight of them on death row for another man's crime . Despite their innocence, news that he was considering the pardon was poorly received in the Panhandle and cost him votes in his 1974 re-election. At the time, Pitts, 31, and Lee, 40, walked out of prison. The state gave them $100 each.

Wilbert Lee and Freddie Pitts (left) were beaten, denied legal counsel, and threatened with death if they didn't sign "confessions" for the 1963 robbery and murder of two Port St. Joe gas station attendants. Within 28 days, an all white jury, white judge, white prosecutor, white policeman -- convicted both of them, sending them off to die in Florida's electric chair. While all this transpired, the real killer, Curtis Adams Jr., a white man who had already been convicted of another murder continued his killing spree. Florida's governor Reubin Askew, who served from 1971 through 1978, in 1975 approved a full pardon for Freddie Pitts and Wilbert Lee, who had spent 12 years in prison, eight of them on death row for another man's crime . Despite their innocence, news that he was considering the pardon was poorly received in the Panhandle and cost him votes in his 1974 re-election. At the time, Pitts, 31, and Lee, 40, walked out of prison. The state gave them $100 each.

Pulitzer-prizewinning Reporter Gene Miller of the Miami Herald began an investigation that helped win a new trial for Pitts and Lee in 1972. The two men were so hopeful about the outcome that just before their second trip to court, they passed up a chance to join a jailbreak. But Adams refused to repeat his confession on the stand, the tape made by the lie detector expert was barred as hearsay evidence, and the all-white jury took only 90 minutes to find Pitts and Lee guilty of murder all over again. They would have been convicted, said a shaken defense attorney, even "if the Twelve Apostles testified for them." Refusing to give up, Miller* and others continued to fight until Governor Reubin Askew agreed to order a new investigation a year and a half ago. Askew personally participated in part of the inquiry and sent his legal aide to talk with Adams. He confessed again, recanted and then confessed a third time to Florida Attorney General Robert Shevin.

"I thought there was our case and maybe a few others like it. But last fall I went to a conference at Northwestern University in Illinois and found 30 others who were innocent and got released. I was shocked! And there are others. Who knows how many didn't get out because they couldn't get the legal help or had no outside support?" - Wilbert LeeCorrection: The Florida Commission on Capital Cases issued a study that listed 23 inmates on death row in Florida who were wrongfully convicted. One more died while on death row who was innocent. And one was released shortly after the study was finished. That makes for 25 wrongfully convicted persons on Florida's Death Row, according to authorities. Frank Lee Smith was not included amongst the 23

.

Joseph Green Brown (left) - In 1974, a Hillsborough County jury convicted him of raping and murdering Earlene Treva Barksdale, a clothing store owner and wife of a prominent Tampa lawyer. The case hinged on Ronald Floyd, a man who held a grudge against Brown because Brown once turned him in for a robbery. The jury also got to see a purported smoking gun, a .38-caliber handgun that prosecutor Robert Bonanno said was the murder weapon, even though an FBI ballistics expert said the handgun could not possibly have fired the fatal bullet -- a witness the jury never heard from. Several months later, Floyd admitted that he lied but Florida courts granted no relief.In the fall of 1983, Gov. Bob Graham signed a death warrant. Brown’s mother suffered a stroke. Brown was within 15 hours of death, forced to listen to technicians in Florida’s death house test the electric chair in which they were about to kill him, when a federal judge in Tampa issued a stay. Asked if there were any particular indignities he was subjected to on death row," Mr. Brown answered,

Joseph Green Brown (left) - In 1974, a Hillsborough County jury convicted him of raping and murdering Earlene Treva Barksdale, a clothing store owner and wife of a prominent Tampa lawyer. The case hinged on Ronald Floyd, a man who held a grudge against Brown because Brown once turned him in for a robbery. The jury also got to see a purported smoking gun, a .38-caliber handgun that prosecutor Robert Bonanno said was the murder weapon, even though an FBI ballistics expert said the handgun could not possibly have fired the fatal bullet -- a witness the jury never heard from. Several months later, Floyd admitted that he lied but Florida courts granted no relief.In the fall of 1983, Gov. Bob Graham signed a death warrant. Brown’s mother suffered a stroke. Brown was within 15 hours of death, forced to listen to technicians in Florida’s death house test the electric chair in which they were about to kill him, when a federal judge in Tampa issued a stay. Asked if there were any particular indignities he was subjected to on death row," Mr. Brown answered,

"One time was just before I was to be executed. They came to measure me for a burial suit. While I stood there, they put the tape measure around my chest, and around my waist, and then they measured the inseam. They did it in such a mechanical way, as if I were an inanimate object. I thought to myself, no, no, this is enough. It was like a ritual about killing me. I struck out, and then the guards hit me in the mouth. That's how I lost my front teeth. They beat me, even though they were going to kill me in less than 24 hours. But I wanted them to know I was a human being, with feelings."Two and a half years later, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the conviction, ruling the prosecution knowingly allowed false testimony from the states’s star witness. One year later, Brown was released after the Hillsborough State Attorney’s Office decided not to retry him. was sentenced to death after having been falsely convicted or a murder, rape and robbery. The only evidence against him was the testimony of Ronald Floyd, a man who held a grudge against him because he had previously turned him into the police on an unrelated crime. At trial, Floyd denied that there was any deal for his testimony and the prosecution repeatedly emphasized to the jury that Floyd had no deal. Several months after trial, Floyd admitted that he had lied at trial, and that he had testified in return for not being prosecuted himself for the murder, and for a light sentence on another crime.

Willie A. Brown (l) and Larry Troy(r) were convicted of first-degree murder and both sentenced to death. The conviction was based entirely upon the testimony of another prisoner who testified that he saw them leave the victim's cell shortly before his body was discovered. A German anti-death-penalty activist took an interest in the case and, fitted with a hidden microphone, obtained an admission from the witness, Frank Wise, that he had lied about the two men's involvement. The witness was then convicted of perjury and Messrs. Brown and Troy were released after spending five years on death row. Brown is African American, the victim Caucasian. Anibal Jaramillo, an illegal Colombian immigrant, was convicted for the murders of Gilberto Caicedo and Candellario Castellanos and sentenced to death. The prosecution's case was built on the fact that Jaramillo's fingerprints were found on a knife casing, a table, and grocery bag in the victims' home. At trial, Jaramillo explained that he had been in the victims' home earlier that day and had helped the victims' nephew cut open some boxes, and evidence emerged that tended to incriminate the victims’ roommate, but the jury convicted him nonetheless. The victims' nephew was unavailable to corroborate or contradict Jaramillo's testimony, as he could not be located. Dade Circuit Judge Ellen Morphonios-Gable overruled the jury’s recommendation of life in prison. On appeal, the Florida Supreme Court ruled that the prosecution evidence was completely inadequate to support a conviction, and ordered Jaramillo's acquittal in 1982. The day Jaramillo left death row, the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms arrested him for lying on a form when he bought a .45-caliber pistol from a gun shop in 1980. In 1983, a federal judge sentenced him to four years in prison. Jaramillo was eventually deported to Colombia, where he was murdered in Medellin.

Willie A. Brown (l) and Larry Troy(r) were convicted of first-degree murder and both sentenced to death. The conviction was based entirely upon the testimony of another prisoner who testified that he saw them leave the victim's cell shortly before his body was discovered. A German anti-death-penalty activist took an interest in the case and, fitted with a hidden microphone, obtained an admission from the witness, Frank Wise, that he had lied about the two men's involvement. The witness was then convicted of perjury and Messrs. Brown and Troy were released after spending five years on death row. Brown is African American, the victim Caucasian. Anibal Jaramillo, an illegal Colombian immigrant, was convicted for the murders of Gilberto Caicedo and Candellario Castellanos and sentenced to death. The prosecution's case was built on the fact that Jaramillo's fingerprints were found on a knife casing, a table, and grocery bag in the victims' home. At trial, Jaramillo explained that he had been in the victims' home earlier that day and had helped the victims' nephew cut open some boxes, and evidence emerged that tended to incriminate the victims’ roommate, but the jury convicted him nonetheless. The victims' nephew was unavailable to corroborate or contradict Jaramillo's testimony, as he could not be located. Dade Circuit Judge Ellen Morphonios-Gable overruled the jury’s recommendation of life in prison. On appeal, the Florida Supreme Court ruled that the prosecution evidence was completely inadequate to support a conviction, and ordered Jaramillo's acquittal in 1982. The day Jaramillo left death row, the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms arrested him for lying on a form when he bought a .45-caliber pistol from a gun shop in 1980. In 1983, a federal judge sentenced him to four years in prison. Jaramillo was eventually deported to Colombia, where he was murdered in Medellin.

Anthony Silah Brown, was sentenced to death after having been convicted of murder. At trial, the only evidence against Brown was a co-defendant who was sentenced to life for his part in the crime. After returning a guilty verdict, the jury recommended a life sentence for Mr. Brown, but the trial judge overrode this recommendation and imposed a sentence of death. At retrial, the co-defendant admitted that his testimony at the first trial had been perjured, and Brown was acquitted, after spending three years on death row, who watched and listened 12 times as guards prepared for executions.

Juan Ramos (left) grew up in Cuba and came to Florida in the 1980 Mariel boat lift. Within a year, he was married, and working in a steel factory. In June 1982, police arrested him for raping and murdering Sue Cobb, 27, who lived a block away. There was no physical evidence that linked Ramos to the homicide, but the police dog, after sniffing an empty pack of Ramos' cigarettes, and subsequently put in a room with five knives and five blouses, stopped at blouse No. 5, the victim's bloody blouse, then licked knife No. 3, the bloody knife that had killed her. However, only that knife and that blouse had blood on them, which only proved that the dog liked blood. That was enough for a jury to convict Ramos, who barely spoke English, and for a judge to overrule its recommendation of life and sentence him to death.

Juan Ramos (left) grew up in Cuba and came to Florida in the 1980 Mariel boat lift. Within a year, he was married, and working in a steel factory. In June 1982, police arrested him for raping and murdering Sue Cobb, 27, who lived a block away. There was no physical evidence that linked Ramos to the homicide, but the police dog, after sniffing an empty pack of Ramos' cigarettes, and subsequently put in a room with five knives and five blouses, stopped at blouse No. 5, the victim's bloody blouse, then licked knife No. 3, the bloody knife that had killed her. However, only that knife and that blouse had blood on them, which only proved that the dog liked blood. That was enough for a jury to convict Ramos, who barely spoke English, and for a judge to overrule its recommendation of life and sentence him to death.  In October 1985, 20/20 exposed the unreliability of scent-tracking dogs, including the German shepherd that put Ramos behind bars. The dogs and their trainer, several times, identified suspects who were innocent. In August 1986, the Florida Supreme Court granted Ramos a new trial because of the prosecution's improper use of evidence and at retrial, Ramos was acquitted. O n April 24, 1987, after spending five years on death row, where he learned to speak English, Ramos walked out a free man.

In October 1985, 20/20 exposed the unreliability of scent-tracking dogs, including the German shepherd that put Ramos behind bars. The dogs and their trainer, several times, identified suspects who were innocent. In August 1986, the Florida Supreme Court granted Ramos a new trial because of the prosecution's improper use of evidence and at retrial, Ramos was acquitted. O n April 24, 1987, after spending five years on death row, where he learned to speak English, Ramos walked out a free man.

Anthony Ray Peek (left) was twice convicted of murder and sentenced to death, the first time, on May 3, 1978 for the rape and strangulation of a Winter Haven nurse, despite witnesses who supported his alibi. The white judge who presided over the trial demonstrated prejudgments when he said, "Since the nigger mom and dad are here anyway, why don't we go ahead and do the penalty phase today instead of having to subpoena them back at the cost of the state." [Debating the Death Penalty, p. 87] Peeks remained on death row in Florida for nine years, from 1978 until 1987. It was later shown that the prosecution's expert witness had lied about test results and that the hair found at the scene did not match Peek's hair. His conviction was overturned and he was acquitted at his third retrial in 1987.

Anthony Ray Peek (left) was twice convicted of murder and sentenced to death, the first time, on May 3, 1978 for the rape and strangulation of a Winter Haven nurse, despite witnesses who supported his alibi. The white judge who presided over the trial demonstrated prejudgments when he said, "Since the nigger mom and dad are here anyway, why don't we go ahead and do the penalty phase today instead of having to subpoena them back at the cost of the state." [Debating the Death Penalty, p. 87] Peeks remained on death row in Florida for nine years, from 1978 until 1987. It was later shown that the prosecution's expert witness had lied about test results and that the hair found at the scene did not match Peek's hair. His conviction was overturned and he was acquitted at his third retrial in 1987.

Herman Lindsey, the 135th person to be exonerated from death row, and the fifth person in 2009, was acquitted and released on July 9, 2009. The Florida Supreme Court ruled unanimously (7-0) “the state failed to produce any evidence in this case placing Lindsey at the scene of the crime at the time of the murder,” and that the evidence presented was “equally consistent with a reasonable hypothesis of innocence.” Lindsey was arrested for the murder of an employee at the Big Dollar Pawn Shop in Fort Lauderdale, in 2006, 12-years after the crime. The trial court erred by allowing the jury to hear "inflammatory" statements from the prosecutor that unfairly led to a death sentence as well. "I conclude that this error was not harmless. The prosecution's comments were not only improper, but were also prejudicial and made with the apparent goal of inflaming the jury," Justice Peggy Quince wrote in an opinion.

Herman Lindsey, the 135th person to be exonerated from death row, and the fifth person in 2009, was acquitted and released on July 9, 2009. The Florida Supreme Court ruled unanimously (7-0) “the state failed to produce any evidence in this case placing Lindsey at the scene of the crime at the time of the murder,” and that the evidence presented was “equally consistent with a reasonable hypothesis of innocence.” Lindsey was arrested for the murder of an employee at the Big Dollar Pawn Shop in Fort Lauderdale, in 2006, 12-years after the crime. The trial court erred by allowing the jury to hear "inflammatory" statements from the prosecutor that unfairly led to a death sentence as well. "I conclude that this error was not harmless. The prosecution's comments were not only improper, but were also prejudicial and made with the apparent goal of inflaming the jury," Justice Peggy Quince wrote in an opinion.

William Jent and Ernest Miller, half brothers, were sentenced to death for the rape and murder of an unidentified woman whose badly burned body was found in a Pasco County, Florida, game preserve in July of 1979. The sherrif's department coerced the two women the brothers were seen with the night of the murder, to provide testimony that they saw the brothers beat the victim until she collapsed, put her into the trunk of a car, drive to a game preserve, and set the body afire, in order to provide enough evidence to arrest the two "available and disposable" [“Symposium on the Underclass,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 136.3 (1992): 319–52.] young men. The brothers came within 16 hours of execution in 1983 before winning a stay from a federal judge because the prosecution had withheld exculpatory information. In 1986, the victim finally was identified and it was determined that her death occurred at a different time than the eyewitnesses had contended. The defendants had a solid alibi. Moreover, it turned out, the victim's former boyfriend had been convicted in Georgia of an eerily similar crime. A new trial was then ordered, but prosecutors refused to drop the charges. The state of Florida didn't want to admit a travesty of justice had occurred and the two men didn't want to risk another trial. So, in 1988, the defendants pled guilty to second-degree murder in order to be released immediately from prison. Once free, however, they repudiated the pleas. The original witnesses subsequently made statements indicating that they had been coerced by sheriff's officers to fabricate the story presented at trial. In 1991, the Pasco County Sheriff's Department paid the men $65,000 to settle civil rights claims.

Robert Craig Cox was convicted of murdering a nineteen-year old woman and subsequently sentenced to death. The evidence against him was entirely circumstantial. Cox stayed at the same motel where the victim's body was found. He cut his tongue that night, and hair and blood samples found near the victim were generally compatible with those of Cox. ( 0+, a trait shared by 45% of the population.) A boot print at the crime scene was consistent with a military boot and Cox had a military job. On appeal, the Supreme Court of Florida unanimously reversed Cox's conviction. The Court ordered that Cox be released immediately

Robert Craig Cox was convicted of murdering a nineteen-year old woman and subsequently sentenced to death. The evidence against him was entirely circumstantial. Cox stayed at the same motel where the victim's body was found. He cut his tongue that night, and hair and blood samples found near the victim were generally compatible with those of Cox. ( 0+, a trait shared by 45% of the population.) A boot print at the crime scene was consistent with a military boot and Cox had a military job. On appeal, the Supreme Court of Florida unanimously reversed Cox's conviction. The Court ordered that Cox be released immediately

.

Bradley P. Scott was convicted of murdering a 12-year old girl, and sentenced to death, despite the police ruling him out initially as he had a sound alibi--he was with his girlfriend shopping at the mall at the time. Seven years later a new sheriff reopened the investigation. His arrest came ten years after the crime, when the evidence corroborating his alibi had been lost, so Scott was convicted on the testimony of witnesses whose identifications had been plagued with inconsistencies. On appeal, he was released by the Florida Supreme Court, which found that the evidence used to convict Scott was not sufficient to support a finding of guilt.

Bradley P. Scott was convicted of murdering a 12-year old girl, and sentenced to death, despite the police ruling him out initially as he had a sound alibi--he was with his girlfriend shopping at the mall at the time. Seven years later a new sheriff reopened the investigation. His arrest came ten years after the crime, when the evidence corroborating his alibi had been lost, so Scott was convicted on the testimony of witnesses whose identifications had been plagued with inconsistencies. On appeal, he was released by the Florida Supreme Court, which found that the evidence used to convict Scott was not sufficient to support a finding of guilt.

Andrew Golden, a former teacher, and law-abiding citizen, who was married to his wife, Ardelle, for twenty-four years, and with whom he had two sons, was sent to death row in 1991 for allegedly drowning his wife, despite the police investigators and medical examiner who stated at trial that the evidence did not suggest foul play. Her death was initially ruled accidental. Golden's lawyer did almost nothing to prepare for trial, having assumed that he would have the case thrown out beforehand. When the case was announced for trial, it was too late to prepare. The attorney put on no defense. He never presented the jury with the reasonable explanation that Golden's wife might have committed suicide, having been depressed over the recent death of her father. He never told the jury about the coffee mug wedged near the brake and accelerator pedal, or the four death notices of her father which Ardelle had with her in the car. The jury accepted the prosecution's theory that Golden pushed his wife off the dock in order to get insurance money. The jury was never told that the water by the dock was not even over Ardelle's head. On appeal, the Florida Supreme Court unanimously decided that the prosecution had failed to prove that Ardelle's death was anything but an accident. After two years on death row, he was freed in 1994.

Sonia Jacobs and her boyfriend, Jesse Tafero, were sentenced to death for the murder of Florida Highway Patrol Trooper Phillip Black in 1976. Walter Rhodes, who was also with them was the only one who tested positive for gunpowder residue. But after he agreed to testify against Jacobs and Tafero, he got a life sentence. They were sentenced to die. Jacobs spent the next five years in solitary confinement. She meditated and practiced yoga. She said, "I figured if people could survive the concentration camps, then surely I could survive this." In 1981, the Florida Supreme Court commuted Jacobs' sentence to life in prison after her lawyers uncovered a polygraph test suggesting that Rhodes, the prosecution's chief witness, might have lied. The next year, Rhodes recanted, saying he -- not Jacobs or Tafero -- pulled the trigger. Tafero was executed in May, 1990.

Sonia Jacobs and her boyfriend, Jesse Tafero, were sentenced to death for the murder of Florida Highway Patrol Trooper Phillip Black in 1976. Walter Rhodes, who was also with them was the only one who tested positive for gunpowder residue. But after he agreed to testify against Jacobs and Tafero, he got a life sentence. They were sentenced to die. Jacobs spent the next five years in solitary confinement. She meditated and practiced yoga. She said, "I figured if people could survive the concentration camps, then surely I could survive this." In 1981, the Florida Supreme Court commuted Jacobs' sentence to life in prison after her lawyers uncovered a polygraph test suggesting that Rhodes, the prosecution's chief witness, might have lied. The next year, Rhodes recanted, saying he -- not Jacobs or Tafero -- pulled the trigger. Tafero was executed in May, 1990.

When Sonia "Sunny" Jacobs went to prison for murder in 1976, her son was 9. Her daughter, 10 months old, was still nursing. When she was freed in 1992, her son was married with a child of his own and her daughter was a 16-year-old stranger. "Getting back family is the hardest part," says Jacobs, now 51, who teaches yoga and lives in Los Angeles. "They live with embarrassment for so long: You say you didn't (commit the murder), but everyone says you did."A childhood friend of Jacobs, filmmaker Micki Dickoff, became interested in her case. Using court transcripts, affidavits and old newspaper stories, Dickoff found discrepancies in testimony and put together a color-coded brief for the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. It was enough to overturn Jacobs' conviction.

James Richardson, a poor migrant farm worker, was sentenced to death after being convicted of murdering Richardson was convicted and sentenced to death for the poisoning of one of his children. The prosecution argued that Richardson committed the crime to obtain insurance money, despite the fact that no such policy existed. The primary witnesses against Richardson were two jail-house snitches whom Richardson was said to have confessed to. Post-conviction investigation found that the neighbor who was caring for Richardson's children had a prior homicide conviction, and the defense provided affidavits from people to whom he had confessed. Richardson's conviction was overturned after further investigation by then-Dade County State Attorney General Janet Reno, which resulted in a new hearing.

James Richardson, a poor migrant farm worker, was sentenced to death after being convicted of murdering Richardson was convicted and sentenced to death for the poisoning of one of his children. The prosecution argued that Richardson committed the crime to obtain insurance money, despite the fact that no such policy existed. The primary witnesses against Richardson were two jail-house snitches whom Richardson was said to have confessed to. Post-conviction investigation found that the neighbor who was caring for Richardson's children had a prior homicide conviction, and the defense provided affidavits from people to whom he had confessed. Richardson's conviction was overturned after further investigation by then-Dade County State Attorney General Janet Reno, which resulted in a new hearing.

Robert Hayes was convicted of rape and murder and was sentenced to death. The prosecution presented testimony that placed him with the victim, at the time that the murder took place. The prosecution also introduced DNA evidence that supposedly linked Mr. Hayes to the crime. A new trial was ordered because of faulty DNA analysis that rendered it unreliable and contaminated. At the second trial, evidence emerged that the victim was found clutching hairs of a white ma; Hayes is African-American. Evidence also emerged of the possibility of another suspect. After six years on death row, the jury at the second trial acquitted Mr. Hayes of all charges.

Robert Hayes was convicted of rape and murder and was sentenced to death. The prosecution presented testimony that placed him with the victim, at the time that the murder took place. The prosecution also introduced DNA evidence that supposedly linked Mr. Hayes to the crime. A new trial was ordered because of faulty DNA analysis that rendered it unreliable and contaminated. At the second trial, evidence emerged that the victim was found clutching hairs of a white ma; Hayes is African-American. Evidence also emerged of the possibility of another suspect. After six years on death row, the jury at the second trial acquitted Mr. Hayes of all charges.

Joseph Spaziano was tried for the murder of a young woman which had occurred two years earlier. No physical evidence linked him to the crime. He was convicted primarily on the testimony of a drug-addicted teenager who, after hypnosis and "refreshed-memory" interrogation, thought he recalled Spaziano describing the murder. This witness has recently said that his testimony was totally unreliable and not true. Hypnotically induced testimony is no longer admissible in Florida. Death warrants have been repeatedly signed for Spaziano, even though the jury in his case had recommended a life sentence. In January, 1996, Florida Circuit Court Judge O.H. Eaton granted Spaziano a new trial, and this decision was upheld by the Florida Supreme Court on April 17, 1997. In November, 1998, Spaziano pleaded no contest to second degree murder and was sentenced to time served. He remains incarcerated on another charge.

Joseph Spaziano was tried for the murder of a young woman which had occurred two years earlier. No physical evidence linked him to the crime. He was convicted primarily on the testimony of a drug-addicted teenager who, after hypnosis and "refreshed-memory" interrogation, thought he recalled Spaziano describing the murder. This witness has recently said that his testimony was totally unreliable and not true. Hypnotically induced testimony is no longer admissible in Florida. Death warrants have been repeatedly signed for Spaziano, even though the jury in his case had recommended a life sentence. In January, 1996, Florida Circuit Court Judge O.H. Eaton granted Spaziano a new trial, and this decision was upheld by the Florida Supreme Court on April 17, 1997. In November, 1998, Spaziano pleaded no contest to second degree murder and was sentenced to time served. He remains incarcerated on another charge.

Joseph Nahume Green was convicted of the 1992 killing of the society page editor of the weekly Bradford County Telegraph and sentenced to death primarily on the testimony of Lonnie Thompson, the state's only eyewitness, who was "often inconsistent and contradictory." according to the ruling of the Florida Supreme Court. Thompson, with an IQ of 67 is mildly retarded and has suffered head traumas that have caused memory problems. Thompson also admitted to drinking 8 cans of beer and using cocaine and marijuana before the shooting. He also told police at first that a white man shot the victim. Green is black. On March 16, 2000, Green was acquitted of the murder of Judith Miscally. Circuit Judge Robert P. Cates entered a not guilty verdict for Green, citing the lack of any witnesses or evidence tying Green to the murder. Green, who has always maintained his innocence, was convicted largely upon the testimony of the state's only eye witness, Lonnie Thompson.

Joseph Nahume Green was convicted of the 1992 killing of the society page editor of the weekly Bradford County Telegraph and sentenced to death primarily on the testimony of Lonnie Thompson, the state's only eyewitness, who was "often inconsistent and contradictory." according to the ruling of the Florida Supreme Court. Thompson, with an IQ of 67 is mildly retarded and has suffered head traumas that have caused memory problems. Thompson also admitted to drinking 8 cans of beer and using cocaine and marijuana before the shooting. He also told police at first that a white man shot the victim. Green is black. On March 16, 2000, Green was acquitted of the murder of Judith Miscally. Circuit Judge Robert P. Cates entered a not guilty verdict for Green, citing the lack of any witnesses or evidence tying Green to the murder. Green, who has always maintained his innocence, was convicted largely upon the testimony of the state's only eye witness, Lonnie Thompson.

John Robert Ballard had served nearly three years for the 1999 murders of Jennifer Jones and Willie Ray Patin Jr. at their Collier County apartment, even though there was little to connect him to the slayings of his friends. Ballard's conviction had been based almost entirely on the discovery of one fingerprint and arm hair being found in the victims' apartment - a place he had visited numerous times. The Florida Supreme Court unanimously overturned the conviction of Death Row inmate John Robert Ballard and ordered his acquittal. The court concluded that the evidence against Ballard was so weak that the trial judge should have dismissed the case immediately. At Ballard’s trial, only 9 of the 12 jurors recommended a death sentence. The judge decided to sentence Ballard to death, commenting, “You have not only forfeited your right to live among us, but under the laws of the state of Florida, you have forfeited your right to live at all.” After serving three years on death row for a crime he did not commit,the State of Florida gave Mr. Ballard a paltry $100 in cash when they freed him after more than 3 years of incarceration on death row. He became the 26th person to be exonerated and released from Florida's death row since 1972.

“Had it not been for what some call pure luck or what I like to think of as miracles, the state of Florida would have killed me.” -Juan Roberto Melendez Exonerated from Florida’s Death RowWe know how rare miracles are so there is no telling how many innocent people have been murdered by the State of Florida.

Georgia:

Almost 34 years ago, July 2, 1976, the Gregg v. Georgia ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty and marked the beginning of the modern period of capital punishment. Four years earlier, the Supreme Court's decision, in Furman v. Georgia, forced states and the national legislature to rethink their statutes for capital offenses to assure that the death penalty would not be administered in a capricious or discriminatory manner and that all existing death penalty statutes were unconstitutional. The justices found that the prevailing pattern of arbitrary imposition of the death penalty could no longer be tolerated. In the words of Justice Potter Stewart, "These death sentences are cruel and unusual in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual" - - they are capriciously, freakishly, and wantonly imposed. The Supreme Court commuted the sentences of all 629 people on death row. For every six people executed in Georgia since 1973, one has been exonerated. Misconduct by police and prosecutors played a major role in Georgia’s death row exoneration cases. And like most of those on death row today, many of Georgia’s wrongfully convicted could not afford a private attorney. Georgia does not guarantee counsel in the appeals process – even if the inmate has new evidence of innocence.

Almost 34 years ago, July 2, 1976, the Gregg v. Georgia ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty and marked the beginning of the modern period of capital punishment. Four years earlier, the Supreme Court's decision, in Furman v. Georgia, forced states and the national legislature to rethink their statutes for capital offenses to assure that the death penalty would not be administered in a capricious or discriminatory manner and that all existing death penalty statutes were unconstitutional. The justices found that the prevailing pattern of arbitrary imposition of the death penalty could no longer be tolerated. In the words of Justice Potter Stewart, "These death sentences are cruel and unusual in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual" - - they are capriciously, freakishly, and wantonly imposed. The Supreme Court commuted the sentences of all 629 people on death row. For every six people executed in Georgia since 1973, one has been exonerated. Misconduct by police and prosecutors played a major role in Georgia’s death row exoneration cases. And like most of those on death row today, many of Georgia’s wrongfully convicted could not afford a private attorney. Georgia does not guarantee counsel in the appeals process – even if the inmate has new evidence of innocence.  One of the most recognizable faces in the fight to make sure those wrongly convicted do not die at the hands of the state is that of Georgia's death row inmate, Troy Anthony Davis. Davis, 38, of Savannah, has faced execution and the death chamber three times in his 18 years on Georgia's death row for the 1989 slaying of off-duty Savannah police officer Mark Allen MacPhail. Since Davis' conviction, the evidence against him has fallen apart. No physical evidence; no murder weapon; seven of the nine witnesses have recanted or contradicted their testimony, many alleging police coercion. Of the two eyewitnesses who stuck to their stories, Sylvester "Redd” Coles was himself considered a suspect in the killing. The other initially told police he could not identify the shooter. After prolonged appeals, the U.S. Supreme Court, on Aug. 17, instructed a federal court in Georgia to consider, for the first time in a formal court proceeding, significant evidence of Davis' innocence that surfaced after his conviction. This is the first such order from the U.S. Supreme Court in almost 50 years. The Supreme Court has never ruled on whether it is unconstitutional to execute an innocent person.

One of the most recognizable faces in the fight to make sure those wrongly convicted do not die at the hands of the state is that of Georgia's death row inmate, Troy Anthony Davis. Davis, 38, of Savannah, has faced execution and the death chamber three times in his 18 years on Georgia's death row for the 1989 slaying of off-duty Savannah police officer Mark Allen MacPhail. Since Davis' conviction, the evidence against him has fallen apart. No physical evidence; no murder weapon; seven of the nine witnesses have recanted or contradicted their testimony, many alleging police coercion. Of the two eyewitnesses who stuck to their stories, Sylvester "Redd” Coles was himself considered a suspect in the killing. The other initially told police he could not identify the shooter. After prolonged appeals, the U.S. Supreme Court, on Aug. 17, instructed a federal court in Georgia to consider, for the first time in a formal court proceeding, significant evidence of Davis' innocence that surfaced after his conviction. This is the first such order from the U.S. Supreme Court in almost 50 years. The Supreme Court has never ruled on whether it is unconstitutional to execute an innocent person.

Where is the Justice for me? A plea from Troy Davis Where is the Justice for me? In 1989 I surrendered myself to the police for crimes I knew I was innocent of in an effort to seek justice through the court system in Savannah, Georgia USA. But like so many death penalty cases, that was not my fate and I have been denied justice. During my imprisonment I have lost more than my freedom, I lost my father and my family has suffered terribly, many times being treated as less than human and even as criminals. In the past I have had lawyers who refused my input, and would not represent me in the manner that I wanted to be represented. I have had witnesses against me threatened into making false statements to seal my death sentence and witnesses who wanted to tell the truth were vilified in court. For the entire two years I was in jail awaiting trial I wore a handmade cross around my neck, it gave me peace and when a news reporter made a statement in the local news, “Cop-killer wears cross to court,” the cross was immediately taken as if I was unworthy to believe in God or him in me. The only time my family was allowed to enter the courtroom on my behalf was during the sentencing phase where my mother and sister had to beg for my life and the prosecutor simply said, “I was only fit for killing.” Where is the Justice for me, when the courts have refused to allow me relief when multiple witnesses have recanted their testimonies that they lied against me? Because of the Anti-Terrorism Bill, the blatant racism and bias in the U.S. Court System, I remain on death row in spite of a compelling case of my innocence. Finally I have a private law firm trying to help save my life in the court system, but it is like no one wants to admit the system made another grave mistake. Am I to be made an example of to save face? Does anyone care about my family who has been victimized by this death sentence for over 16 years? Does anyone care that my family has the fate of knowing the time and manner by which I may be killed by the state of Georgia? I truly understand a life has been lost and I have prayed for that family just as I pray for mine, but I am Innocent and all I ask for is a True Day in a Just Court. If I am so guilty why do the courts deny me that? The truth is that they have no real case; the truth is I am Innocent.

Jerry Banks (left) was tried and convicted twice for the murder of two people in Henry County, Georgia. In both cases, inadequate legal representation and the suppression of exculpatory evidence contributed to Bank’s wrongful convictions. The prosecution withheld evidence from the defense, which included the testimony of several witnesses which contradicted the story put forth by prosecutors at trial. Prosecutors dropped all charges against him when the chief detective in the case was implicated in evidence tampering. Jerry Banks spent six years on death row before new volunteer lawyers got his conviction overturned on the basis of newly discovered evidence. Soon after, the court decision, it was also discovered that the shotgun shells found at the crime scene, which allegedly came from Banks’ gun, were actually planted.

Jerry Banks (left) was tried and convicted twice for the murder of two people in Henry County, Georgia. In both cases, inadequate legal representation and the suppression of exculpatory evidence contributed to Bank’s wrongful convictions. The prosecution withheld evidence from the defense, which included the testimony of several witnesses which contradicted the story put forth by prosecutors at trial. Prosecutors dropped all charges against him when the chief detective in the case was implicated in evidence tampering. Jerry Banks spent six years on death row before new volunteer lawyers got his conviction overturned on the basis of newly discovered evidence. Soon after, the court decision, it was also discovered that the shotgun shells found at the crime scene, which allegedly came from Banks’ gun, were actually planted.

On 7 November 1974, Jerry Banks, then 23 years old, was rabbit hunting when he discovered the bodies of Marvin King and Melanie Hartsfield. Both victims had been shot to death with a shotgun and police found two red shotgun shells at the scene of the crime; Banks was hunting with a shotgun. Banks rushed back to the main road and alerted a passing motorist who in turn alerted the police.